In diretta da Los Angeles, ecco in anteprima la recensione di The Hateful Eight, il nuovo film di Quentin Tarantino al cinema dal 4 febbraio: la firma in esclusiva per Ciak Emanuel Levy, critico per Variety e The Hollywood Reporter, professore di Cinema e Sociologia, autore del sito emanuellevy.com, di molti libri (l’ultimo Gay Directors, Gay Film?) e della speciale Column sul nostro daily dalla Mostra di Venezia CiakinMostraÂ

THE HATEFUL EIGHT: LE IENE NELÂ SELVAGGIO WEST

DI EMANUEL LEVY

È appropriato che l’ottavo film di Quentin Tarantino (come annunciato nei credits) s’intitoli The Hateful Eight, per non parlare del fatto che ha otto protagonisti principali. Rivisitando i temi delle sue opere precedenti, la maggior parte di The Hateful Eight, a dispetto del genere, è ambientato in interni, dove i personaggi sono confinati in uno spazio limitato, come accadeva nella pellicola di debutto di Tarantino, Le Iene. E, come in quello del 1991, il nuovo film vanta un impressionante gruppo di attori, alcuni dei quali hanno lavorato col regista in precedenza.

Mescolando elementi del western classico, compreso Ombre rosse di John Ford (1939), The Hateful Eight è un film che avrebbe potuto essere ambientato in un altro tempo e spazio. Più che in altri suoi film precedenti, questo nuovo procede come un giallo di Agatha Christie (nello specifico, Dieci piccoli indiani), un thriller nel quale l’identità e le motivazioni dei personaggi continuano a cambiare e non sono mai chiari, per volontà del regista. Molti elementi sono vaghi, compresa la collocazione storica – non è chiaro se la storia abbia luogo sei o dodici anni dopo la Guerra Civile; ma davvero non è poi così importante. Tanto più che, come è noto, ne era stata fatta una versione precedente in forma di lettura per palcoscenico, e lo stesso Taratino aveva dichiarato che avrebbe potuto vedere questo lavoro come una produzione teatrale.

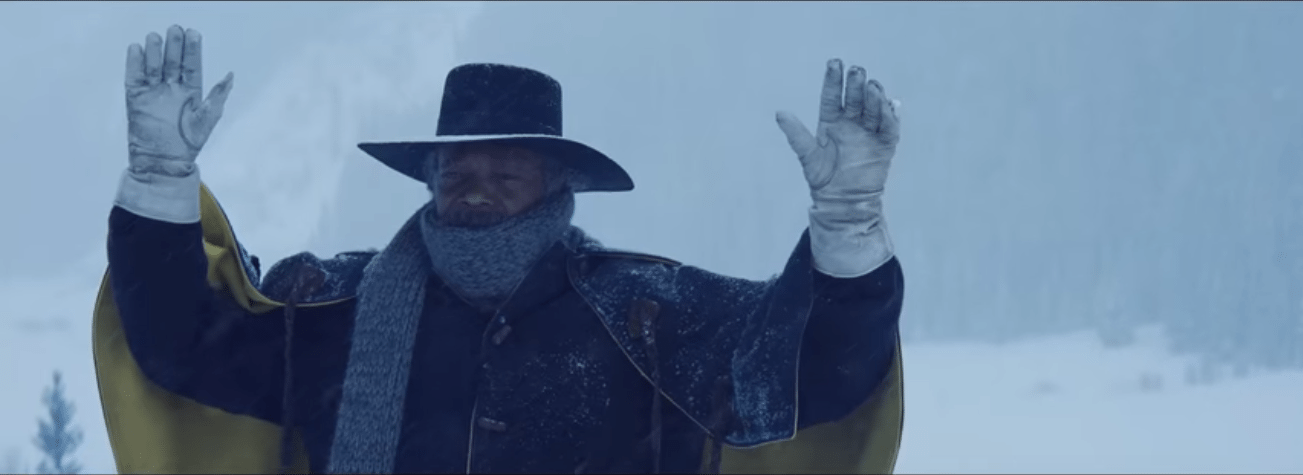

Nella prima scena, che mostra una diligenza che corre attraverso la neve gelida del paesaggio invernale del Wyoming, viene introdotta una strana coppia di passeggeri: John Hurt (Kurt Russell), un cacciatore di taglie, e Daisy Domergue (Jennifer Jason Leigh), la fuggiasca abusata dal primo sia fisicamente che psicologicamente (le femministe potrebbero rimanere disturbate da questo aspetto). Stanno andando alla città di Red Rock dove Ruth, conosciuto come “The Hangman”, minaccia di consegnare Daisy al tipo di “giustizia” che merita.

Lungo la strada, in questo strano road movie, i due incontrano due altri stranieri: il Maggiore Maquis Warren (Samuel L.Jackson), un uomo di colore, ex soldato dell’Unione diventato avido e famigerato cacciatore di taglie, e Chris Mannix (Walton Goggins), un disertore del Sud che dice di essere il nuovo sceriffo della città. Non c’è nessun motivo per credere loro: l’enfasi è sull’auto-percezione e sulla presentazione di sé, non è mai chiaro se i personaggi stiano dicendo la “verità”, o quanto siano basate sui fatti le storie sul loro passato, incluso il vivido ricordo in un flashback in esterni, girato in un glorioso piano sequenza, di espliciti abusi sessuali e razziali tra due uomini.

Perduta la strada a causa di una feroce bufera, Ruth, Domergue, Warren e Mannix cercano rifugio da Minnie’s Haberdashery, un bivacco per diligenze su un passo montano. Che i fiotti di sangue e la sagra delle parole abbiano inizio! Poiché la durata del film è di tre ore (compresi prologo, intermission e musiche di coda), Tarantino prende tempo e lascia i suoi attori pronunciare i loro discorsi quasi senza fine riguardo qualsiasi tipo di argomento caldo, come la politica sessuale, la schiavitù, la giustizia (occhio per occhio) e le relazioni interraziali (ancora: l’uso frequente del termine “negro” potrebbe infastidire Spike Lee), temi che erano esplorati in modo più interessante in Django Unchained (per molti aspetti un film migliore).

La parte più corposa della saga è girata da Minnie’s, dove il quartetto è accolto non dalla proprietaria ma da quattro altre facce sconosciute. Bob (Demian Bichir), che si sta prendendo cura del posto mentre Minnie è in visita a sua madre, si è rifugiato lì insieme a Oswaldo Mobray (Tim Roth), il boia di Red Rock, al cowboy Joe Gage (Michael Madsen) e al vecchio, razzista, per lo più immobile Generale Confederato Sanford Smithers (Bruce Dern).

Visto che nessuno scrive monologhi elaborati tanto quanto Tarantino, presto il film diventa una tortuosa favola di scambi d’identità, motivazioni in conflitto e continui tentativi di indovinare il futuro dei singoli individui, che è pericoloso e incerto. La bufera travolge il bivacco di montagna, costringendo i viaggiatori in uno spazio limitato e pericoloso. A metà strada, loro – e noi spettatori – cominciano a sospettare che quel posto sia una sorta di infernale baita scena scampo, dalla quale nessuno uscirà vivo né riuscirà a raggiungere Red Rock.

Il film mostra ovunque una tensione tra l’ambientazione in interni e la verbosa teatralità dell’impianto narrativo, che è diviso in capitoli (di varia lunghezza), e l’ambizione di fornire all’opera la rispettabilità di un’epopea art house vecchia maniera. Il consueto direttore della fotografia di Tarantino, Robert Richardson, dovrebbe comparire nei credits per aver girato in Panavision 70mm con un rapporto d’immagine 2.76:1, uno stile che non è stato usato a Hollywood dagli anni Sessanta. La gloria visiva e la melanconica colonna sonora (firmata da Ennio Morricone, che prende in prestito liberamente dai suoi lavori del passato) dell’epopea di Tarantino è in 100 cinema americani dal giorno di Natale.

Dal punto di vista commerciale, a The Hateful Eight manca la “pulp fiction” del fantasy di Tarantino sulla Seconda Guerra Mondiale, Inglorious Basterds, e soprattutto la rilevanza sociale e il tono esuberante di Django Unchained, che ha guadagnato 425 milioni di dollari in tutto il mondo ed è il film del regista che ha avuto il maggior successo commerciale. I critici “autorialisti” potrebbero vedere The Hateful Eight come un film che fa coppia con Django Unchained, e forse anche come il frammento di una trilogia iniziata con Inglorious Basterds.

Leggi l’intervista a Quentin Tarantino!

Versione inglese

The Hateful Eight: Reservoir Dogs in the Wild Wild West

It is appropriate that the eighth film from Quentin Tarantino (as the credits announce) should be titled The Hateful Eight, not to mention the fact that the film has eight main protagonists. Revisiting themes from his previous films, most of Hateful Eight, despite its genre, is set indoors, where the figures are confined to a limited space, just as they were in his Tarantino’s first feature, Reservoir Dogs. And like that 1991 film, the new one boasts an impressive ensemble of actors, some of whom have worked with him before. Mixing elements of classic Westerns, including John Ford’s 1939 Stagecoach, Hateful Eight is a film that could have been set in another time and place. More than any of his previous films, the new one unfolds as an Agatha Christie mystery (specifically, Ten Little Indians), a thriller in which the identity and motivation of the characters keeps changing and is never clear–by design. A lot of elements are vague, including the historical setting–it’s not clear if the tale takes place six or twelve years after the Civil War; it really doesn’t matter much. Moreover, as is well known, an earlier version was done as stage reading, and Tarantino himself has said that he could see this work as a theatrical production. In the first scene, which shows a stagecoach riding through the wintry snow of the Wyoming landscape, a strange couple of passengers is introduced, John Ruth (Kurt Russell), a bounty hunter, and Daisy Domergue (Jennifer Jason Leigh), his fugitive who is abused by him both physically and emotionally (feminists may be upset by that aspect). They are on their way to the town of Red Rock where Ruth, known as âThe Hangman,â threatens to bring Daisy to the kind of “justice” she deserves. Along the way in this strange road film, they encounter two other strangers: Major Marquis Warren (Samuel L. Jackson), a black former union soldier turned greedy and infamous bounty hunter, and Chris Mannix (Walton Goggins), a southern renegade who claims to be the town’s new Sheriff.  There is no reason to believe: The emphasis is on self-perception and self-presentation, as it is never clear if the characters are telling the “truth,” or how factual their stories of their pasts are, including a vivid recollection in an outdoor flashback, seen in a glorious long take, of explicit sexual and racial abuse between two men. Losing their way due to a ferocious blizzard, Ruth, Domergue, Warren, and Mannix seek refuge at Minnie’s Haberdashery, a stagecoach stopover on a mountain pass. Let the blood spurt and the talk fest begin! As running time is three hours (including prologue, intermission and exit music), Tarantino takes his time and lets his actor deliver their lengthy, often eloquent speeches about all kinds of hot-button issues, such as sexual politics, slavery, justice (eye for an eye), and interracial relationships (the frequent use of “nigger” should upset Spike Lee–again), motifs that were more interestingly explored in Django Unchained (a better picture on many levels). The saga’s main section is set at Minnie’s, where the quartet is greeted not by the proprietor but by four other unfamiliar faces. Bob (Demian Bichir), who’s taking care of Minnie’s while she’s visiting her mother, is holed up with Oswaldo Mobray (Tim Roth), the hangman of Red Rock, cow-puncher Joe Gage (Michael Madsen), and an old, racist, largely immobile Confederate General Sanford Smithers (Bruce Dern). Since no one writes such elaborate monologues as Tarantino, soon the film becomes a twisty tale of shifting identities, conflicting motivations, and continuous attempts to figure out the future of the individuals, which is unsafe and uncertain. The storm engulfs the mountainside stopover, constraining the travelers to a limited and dangerous space. Midway they–and we the viewers–begin to suspect that this place is sort of a “no exit” hellish cabin, from which no one would escape alive or make it to Red Rock. Throughout, the film shows tension between the indoor setting and verbose theatricality of the narrative, which is divided into chapters (of various length), and the ambition to lend the picture the respectability of an old-fashioned art house epic. Tarantino’s regular cinematographer, Robert Richardson, should be credited for shooting in Panavision 70mm with a 2.76:1 aspect ratio, a style that has not been not used in Hollywood since the 1960s. The visual glory and melancholy score musical (by Ennio Morricone, who borrows freely from his previous efforts) of Tarantino’s epic will be fully experienced as a “road show” in 100 US theaters on Christmas Day. Commercially speaking, Hateful Eight lacks the pulp fiction of Tarantino’s WWII fantasy, Inglourious Basterds, which was a hot, and especially the social relevance and exuberant tone of Django Unchained, which grossed over $425,000 million globally and is the director’s most commercially successful picture. Auteurist critics may see Hateful Eight as a companion piece to Django Unchained, and perhaps even a panel in a trilogy that began with Inglourious Basterds. Â Â

There is no reason to believe: The emphasis is on self-perception and self-presentation, as it is never clear if the characters are telling the “truth,” or how factual their stories of their pasts are, including a vivid recollection in an outdoor flashback, seen in a glorious long take, of explicit sexual and racial abuse between two men. Losing their way due to a ferocious blizzard, Ruth, Domergue, Warren, and Mannix seek refuge at Minnie’s Haberdashery, a stagecoach stopover on a mountain pass. Let the blood spurt and the talk fest begin! As running time is three hours (including prologue, intermission and exit music), Tarantino takes his time and lets his actor deliver their lengthy, often eloquent speeches about all kinds of hot-button issues, such as sexual politics, slavery, justice (eye for an eye), and interracial relationships (the frequent use of “nigger” should upset Spike Lee–again), motifs that were more interestingly explored in Django Unchained (a better picture on many levels). The saga’s main section is set at Minnie’s, where the quartet is greeted not by the proprietor but by four other unfamiliar faces. Bob (Demian Bichir), who’s taking care of Minnie’s while she’s visiting her mother, is holed up with Oswaldo Mobray (Tim Roth), the hangman of Red Rock, cow-puncher Joe Gage (Michael Madsen), and an old, racist, largely immobile Confederate General Sanford Smithers (Bruce Dern). Since no one writes such elaborate monologues as Tarantino, soon the film becomes a twisty tale of shifting identities, conflicting motivations, and continuous attempts to figure out the future of the individuals, which is unsafe and uncertain. The storm engulfs the mountainside stopover, constraining the travelers to a limited and dangerous space. Midway they–and we the viewers–begin to suspect that this place is sort of a “no exit” hellish cabin, from which no one would escape alive or make it to Red Rock. Throughout, the film shows tension between the indoor setting and verbose theatricality of the narrative, which is divided into chapters (of various length), and the ambition to lend the picture the respectability of an old-fashioned art house epic. Tarantino’s regular cinematographer, Robert Richardson, should be credited for shooting in Panavision 70mm with a 2.76:1 aspect ratio, a style that has not been not used in Hollywood since the 1960s. The visual glory and melancholy score musical (by Ennio Morricone, who borrows freely from his previous efforts) of Tarantino’s epic will be fully experienced as a “road show” in 100 US theaters on Christmas Day. Commercially speaking, Hateful Eight lacks the pulp fiction of Tarantino’s WWII fantasy, Inglourious Basterds, which was a hot, and especially the social relevance and exuberant tone of Django Unchained, which grossed over $425,000 million globally and is the director’s most commercially successful picture. Auteurist critics may see Hateful Eight as a companion piece to Django Unchained, and perhaps even a panel in a trilogy that began with Inglourious Basterds. Â Â