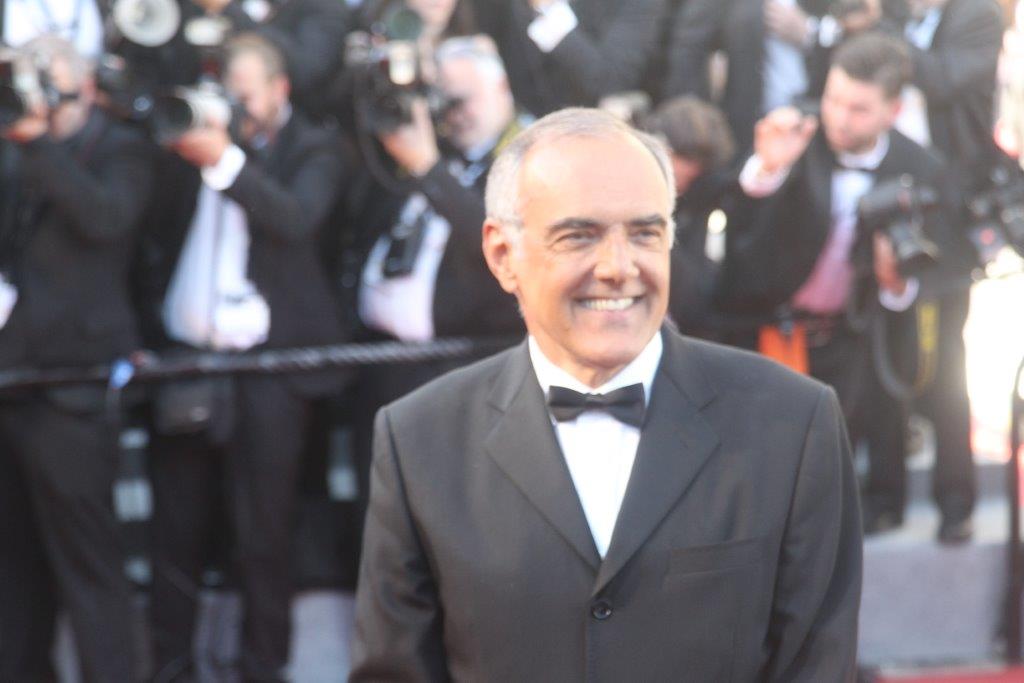

The new name “Boundless”, for the section that was more modestly called “Cinema in the Garden”, says a lot about director Alberto Barbera’s feelings for his festival and could also be a metaphor for it. “You immediately understand what it is about: first-time films, more for film buffs, with even a touch of pop” says Barbera. “The festival on the Lido is an event that has become more open to taking risks. In all the other major festivals, I see a greater resistance to having the courage of your convictions”.

Are you referring to the controversy about the Netflix films that were banned by Cannes and welcomed in Venice?

In part. The past eighteen years have changed the audio-visual world. There have been two reactions: “cinema is dead” or “cinema has become unrecognisable”, but it’s an inevitable mutation. The first people to see perspective in art probably didn’t understand anything about perspective and the viewers who saw the Lumière brothers’ famous train were terrified of being hit by it. The festival is trying to understand the transformation. You shouldn’t build walls and barriers, but understand how to turn these changes into opportunities.”

You’ve been accused of having chosen just one film directed by a woman in competition. You responded that you would resign if quotas were imposed. That’s pretty incendiary in the wake of #MeToo.

I choose films, possibly beautiful and innovative ones, for a festival. I am not interested in politics and I am not a producer. Out of 3300 films viewed for the festival, 23% were by female directors and in the end, across all sections of the festival programme, 22% of the films are by women. There is an enormous problem regarding access and equal opportunities. There is discrimination: producers and financers obviously don’t want to take risks. It is also a political battle, a subject that needs to be put to producers, but it can’t be solved by imposing quotas on the selection. Art can’t contemplate quotas.

I still think it is a strange coincidence that the only film by a woman in the official competition, Jennifer Kent’s Nightingale, is a revenge movie. Or did you do it on purpose in an act of self-flagellation?

(Laughs) No! It is a really powerful film, never banal. It is violent and yet more linguistically refined than her previous cult movie Babadook. It’s about a woman and an aborigine, both excluded in the Tasmania of 1825, who meet. It’s not to be missed.

An exhibition at the Hotel des Bains, itself currently undergoing a resurrection, is showing the history of 75 years of the festival. Since 2010, and the period of the “hole” and the asbestos, you have done a titanic job. How did you do it?

The festival went through a long phase of immobility, of political vetoes, the swamp of the para-state, which saw Venice as an extraneous body. The Biennale president Paolo Baratta managed to free it of all those conditionings, finally creating a dialogue with the regional and city councils. We now have a cinema citadel because there was an open institutional and managerial dialogue. What still needs to be done? The Casino still needs restructuring, hopefully with the addition of a 500-seat screening room, which we need.

How would you sum up the Italian films in competition this year?

The films by Martone, Guadagnino and Minervini take three distinct and opposing directions: in my opinion it is a great opportunity, the confirmation that finally our cinema is experimental, is not limited to repeating antiquated models of the past and has a more international outlook.

Apart from the better-known directors, such as the Coen brothers, Cuaron, Chazelle etc, what are your tips for more lesser-known films that we shouldn’t miss?

The Mountain is visually incredible; every scene is a painting. Jeff Goldblum and Tye Sheridan are excellent as the doctor and his assistant who go around mental hospitals, trying out a cruel cure for mental illness while in tandem there’s the story of the ill and ‘erased’ Kennedy sister. Brady Corbett’s Lux Vox with Natalie Portman, is a hard-hitting surprise; another tense story is the Argentine Acusada, vaguely inspired by the Amanda Knox case. Then there’s Assayas with Doubles Vies, perhaps his best film, an intelligent reflection on the new digital world. I’ve already mentioned Nightingale. My advice is not to miss the docs out of competition, two in particular: They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead, about the torturous making of Orson Welles’s film, The Other Side of the Wind, making its international debut here in Venice, and Peter Bogdanovich’s film A Great Buster about Keaton, a documentary about the artist and the man containing magnificent footage never seen before. It is testimony to the power of film that acts as a riposte to any possible criticism.