What was the retrospective at the Venice Film Festival that was most talked about and circulated in most countries? The answer is surprising. In 2004, Marco Muller became the festival’s artistic director and announced a retrospective of Italian genre cinema in collaboration with the Prada Foundation. This retrospective would have travelled to Milan, London, Melbourne, and Tokyo soon after. The title is decidedly blasphemous: Secret History of Italian Cinema. For militant cinephiles, up to that point, “Secret History” was about postwar Japan and was the title of a fierce film signed by Nagisa Oshima, still in his “political” phase, before becoming an icon of eroticism with The Empire of the Senses. Even more irreverent was the presentation press conference, with Muller announcing that he would receive during his speech the desired confirmation that the most crucial title in the retrospective was indeed screenable. A few minutes later, in a studied move, Marco Giusti (one of the program’s curators) provides the long-awaited confirmation: W la Foca with Lory Del Santo (and the inimitable catchphrase, “may God bless her”) will be there, the program is safe…

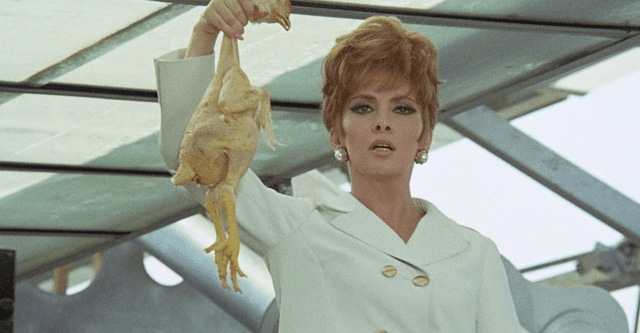

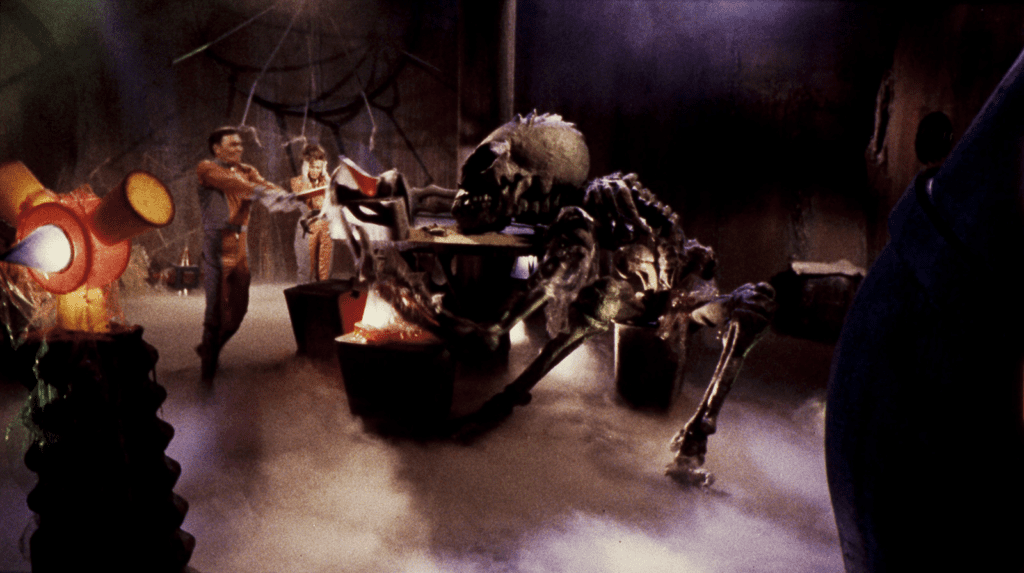

These provocations shook the lethargy of critics. Some are tearing up: Why are junk films reevaluated when other more “important” films are invisible? The answer was twofold. On the one hand, it was astonishing that it was noticed that there was no excellent print of No Peace Among the Olive Trees, only when “poliziotteschi” and westerns were shown. On the other, it was pointed out that inside the review, there were not only W la foca or La guerra di Troia, but also the masterpieces of experimental cinema by Baruchello, Grifi and Schifano, the most important names of the Italian underground. There had already been some warning the previous year when the retrospective dedicated to the great Italian producers included Mario Bava’s Terrore nello spazio (representing the doyen Fulvio Lucisano) and La morte ha fatto l’uovo (with Gina Lollobrigida devoured by actual white chickens…) produced by Marina Cicogna. But with the secret history of Italian cinema, imagination went over: it was a scandal, an offence to culture….

And yet… and yet then everyone noticed that the theatres dedicated to that curious mix of commercial films and experimental works were always full and very often insufficient to accommodate all the audiences. People were bivouacking so as not to miss a single frame of the detective films of Fernando Di Leo, the most celebrated auteur. And when an interminable and boring European “art” film appalled the audience in the Sala Perla, a liberating cry went up. It was greeted by applause similar to that obtained by Paolo Villaggio with his review of Eisenstein’s masterpiece. The shout was, “Give us Orgasm,” and it was not a quote from Bataille but the title of the erotic thriller directed by Umberto Lenzi that was scheduled immediately afterwards at the stroke of midnight. Besides, how could we forget the guests? Directors like Umberto Lenzi or Sergio Martino, who never, ever thought they would be guests at a festival, were pampered, admired, interviewed, and carried in the palm of their hands. They were the stars. The applause over the titles fell to Riccardo Freda, Giorgio Ferroni, and Antonio Margheriti. When in the lobby of the Casino building (thus in one of the high-attendance places), Quentin Tarantino bent his knee in front of Enzo G.Castellari shouting, “Maestro! Maestro!” only the hard-hearted (or envious) were not moved. A few years later, Inglourious Basterds, the remake of Castellari’s That Damn Armored Train, would come from that bow. It was the most significant commercial success in the history of the Mostra. So much for those who said those films belonged to a distant, unrepeatable past…